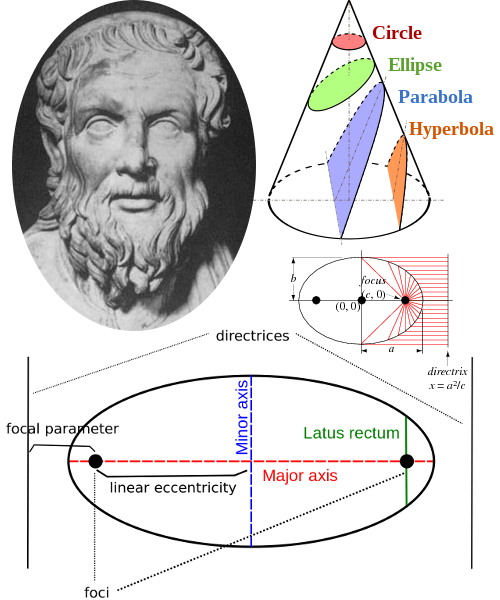

Anatomy of the ellipse

They have been studied extensively as planar sections of a cone (conics) by Apollonius of Perga more that 2000 years ago. He has been considered the autority on this topic through the ages, and even the names, ellipse, hyperbola and parabola go back to him.

http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Apollonius.html

Apollonius threw two points on the plane (called foci), and then defined the ellipse as the set of points (locus in latin) where the sum of the two distances to the foci stays constant:

Imagine you need to get from to but got some more fuel to spend exploring the area. As long as you're driving straight, you can go in any direction as far as to the border of an ellipse, and still make it to your destination. An ellipse is the solution to this detour problem!

A more modern notation is the Cartesian form:

Half the longer axis is called semimajor axis, half the shorter one semiminor axis . "Semi-" because it's only half of an axis. Why is everything in half, why write two times a constant in (1) above? It's to make (2) look fancier, being more popular these days. Here's how you can get from one form to the other:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proofs_involving_the_ellipse

Interestingly, many of the following concepts have analogous counterparts for the other conic sections. Let's get on:

the form

Making an ellipse by scaling a circle by a factor gives a relation between and :

So that the scaling factor is the ratio of over .

By the way, to make shorter than , has to be in the range

Alternatively one can express that is somewhat shorter than and get (related by substitution: ):

And that gives us a parameter equivalent to called flattening:

Wikipedia says that notion goes back to Isaac Newton, who parametrized the shape of spinning water planets that way:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flattening#Origin_of_flattening

An advantage to our cause is, flattening can be related to the eccentricity by this nice looking formula (take square roots if you need to):

You can apply the substitution relation from above, do some calculation, and obtain:

While doing that you might run over something of the form of the pythagorean identity:

So those two parameters can be seen as a point on the unit circle drawn in coordinates, and the corresponding angle (alpha) is then called angular eccentricity:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eccentricity_(mathematics)

the foci

On that page, we get more: The distance from the origin to one of the foci can also be used to quickly calculate the eccentricity :

That distance is also known as linear eccentricity or half-focal separation, the focal separation is the distance between the foci.

The "height in the back" is latus rectum in latin, and a formula for the semilatus rectum is here:

It's related to the periapsis : The length of the shortest way from a focus to the border of our ellipse. That closest point is at the nearest tip, or perihel if you're orbiting the sun.

Similarily, the apoapsis is the greatest possible distance in an ellipse as measured from a focus. At the opposite tip. It's got a nice, similar looking formula:

Clearly, the semimajor axis can be computed as the arithmetic mean of periapsis and apoapsis:

A bit less obvious is that the semiminor axis turns out to be the geometric mean of the two radii:

directrix

Outside the ellipse, orthogonal to lies a line called directrix:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Directrix_(conic_section)#Eccentricity.2C_focus_and_directrix

It can be used to construct an ellipse: The distance of any point on the ellipse to a fixed focus point is proportional to the distance of that point to the directrix. The ratio between them is the eccentricity again:

As a special case, setting we get a relation useful to compute the distance of the directrix from the origin:

Solving for and substituting (10) we get another nice formula worth to mention:

Last but not least, a fun fact about the cycle time for a Kepler ellipse: It does not depend on the length of the minor axis:

It means, a planet will take the same time to go once round the sun no matter what the eccentricity of its orbit is!

Since i have been too lazy to work it out, maybe someone here finds it entertaining. It shouldn't be too hard with what you can look up above. So here is another...

Puzzle: Where does the normal of a tangent to an ellipse in a point meet the major axis?

I can only guess where those latin words had been coined. Nobody say mathematics and relaxing got nothing to do with each other!

other links

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollonius_of_Perga

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conic

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semimajor_axis

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semi-minor_axis

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Focus_(geometry)